In What is Innovation Scouting? we discussed the necessity for organisations to implement innovation scouting into their culture. As these organisations grow and innovation leads become numerous they need to start adding dedicated resources so that leads don’t start falling through the cracks. In this article we present a best practice approach to establishing a structured innovation scouting process.

Innovation is often considered finding the “needle in the haystack”. Consequently many organisations stick with an unstructured reactive approach to finding innovation. The assumption being if they just shout out their needs loud enough and are well connected, then an innovation will appear on the horizon. It should be obvious that the competition for innovation is large and growing constantly, so that this approach is akin to playing the lottery.

Simply copying the processes that thought leaders in the industry have published, or subscribing to one of the many innovation scouting tools and service providers are similarly doomed to failure. Not investing the required work to shape and define your innovation activities means at best low return on your time and money invested and at worst a worse position that you started out with.

“Simply implementing a nicely designed methodology for technology foresight or running weighted queries in a startup database is of little or no value.”

Matteo Fabiano, Firematter (Source)

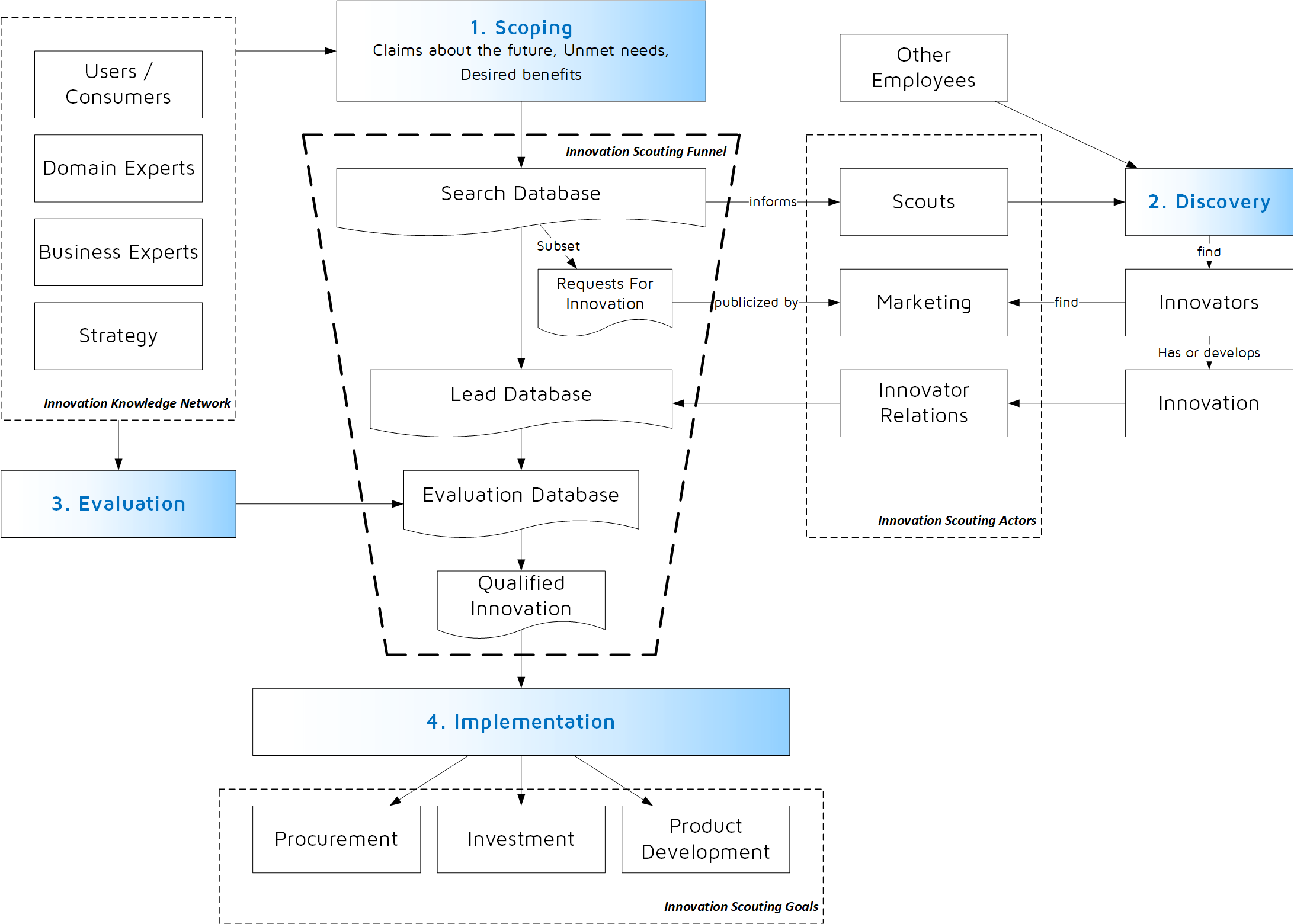

Although the four phases of the innovation scouting funnel being discussed are presented linearly here, they are very much parallel in practice. A classic waterfall approach where the search steps stop and then push the results of that phase into an evaluation and implementation phase is not only wasteful (you might miss out on an important new trend while you are in the following cycles) but you can’t react fast enough to the learnings you acquire in each phase. Borrowed from software development, you innovation processes should be agile with hypothesis testing at the core and repeated questioning of assumptions and course corrections. The primary actors in each step of the innovation scouting process are distinct which also facilitates the parallelism.

Especially the first phase, the definition of the search scopes, should be repeated constantly. It is vastly dependent the organisation, the strategy, the market and the environment, that small changes in this context have magnified impact downstream in the process. Months or even years invested in building an innovative partnership may turn out to be dead on arrival because a certain industry trend that formed the basis has since disappeared

The following diagram shows all four phases of the innovation scouting process with the actors involved. Note the funnel at the center which links the deliverables in each phase to each other. The qualified innovation as the desired results, can be traced back to the evaluations performed, the scouting activity (where did the lead come from) and ultimately back to the search scoped that the innovation need originated from.

Scoping

The scopes for scouting for innovation commonly fall into three categories:

- Claims about the future: an extrapolation of trends or innovative seeds that the organisation discovers through their network or own research.

- Unmet needs: internal or external requirements that are either not met or not met at the desired level (e.g. customers that do not purchase your products or services, for lack of certain functionality, or road block for internal processes)

- Desired benefits: the complement of needs, but rather than a pain that requires solving, these are more often vitamins with improvement potentials (e.g. existing customers requesting additional value or internal processes that could be improved through better tooling)

Each category requires tapping into your “knowledge network”. Neither the innovation managers nor the innovation scouts can be relied on to have the complete picture for this phase. It is their objective to gather this information from the experts. Members of the innovation team should be seen as facilitators of knowledge collection and management, not as oracles.

“scouting needs to follow a methodical and systematic approach, irrespective of the technology in question. There are likely to be hundreds of thousands of technology sources to identify and annotate – even in a focused search – and this requires careful collation and tracking of information for later selection.”

Sagentia (Source)

In this early stage it is important to be open to a vast amount of ideas. It is important for the scout to free themselves from bias on past experience, their own network and influences as much as possible, as any such effect will follow your innovation efforts down to the results.

Often times tools borrowed from market research (e.g. surveys, workshops…) or specific ideation methods (e.g. lead user) will be used to brainstorm or collect ideas for each of the three categories. The knowledge network should find a balance between users/consumers, internal and external business and domain experts with care to at least have a representation of each group. Don’t oversee the obvious opportunities that exist in your own organisation. Front line employees that may have been ignored previously, but can have valuable ideas to improve their daily work. These often carry the potential for high return for very low cost and investment.

The beginning of the scoping phase is marked by a creative freedom without much constraint, similar to formal brainstorming activites, which results in a broad set of ideas. But during the later refinement stages of the search scopes the organisational strategy will play an important role. It is vital that this is certainly a bias being reintroduced, but not at the personal level, as mentioned above, but rather on the organisational level. As an example, an automotive company may have uncovered a great need for solar panels during the early phases, but it requires a rare organisational culture that is very open to such a big departure from the core competency. The plethora of new and unique solutions will need to fit the innovative capability of the organisation it serves.

The scoping phase may profit from some tooling, but keep in mind tooling also restricts the creativity which is so vital in this step. The results usually take on the form of a presentation to management. Once they have given their approval though, tooling should enter the process. The scoping information forms the top of the innovation scouting funnel and description of the agreed upon search scopes, what they mean for the organisation and specifics (very analog to requirements for a software project) are entered into the search database (sometimes referred to as a “claim database”). All future steps and results will ultimately lead back to one of your defined search scopes.

If you follow the manifesto of open innovation you may choose to publish your search scopes to the public (e.g. on your website) in order to display your openness to external participation and to signal your innovative nature. Marketing can be applied to make your innovation needs known and sometimes shortcut the scouting process for leads that find you instead of the other way around. We will look into this topic in a future article.

Discovery

In this step you go from a clear definition of what kinds of innovations you are looking for, to suitable candidates (innovators, innovations and ideas) that can fulfill them. As talked about previously a lead can come from any of the employees in the organisation if the culture supports it, but in the context of a more formal innovation scouting process, this is where innovation scouts spend most of their time.

Depending on the number of search scopes and available innovation scouts each individual may have all of the scopes in the back of their head but concentrate on a few specific ones to concentrate their efforts. When visiting a broad industry conference for instance a scout may find an innovation by coincidence walking around or talking to someone, but will actively search for innovations in their assigned search scopes. But the same applies to searching through databases, news sources and contacts. A good scout is triggered by any suitable innovation, but hunts for specific innovations.

Depending on the number of scouts available and the iterative nature of the process you would choose a subset of the search scopes to work on in each iteration rather than overwhelming each scout with a large number.

Where the search scope is the input to this phase, the connection to a lead is the activity and a dataset of information on that lead is the resulting deliverable. The information received from an innovator has traditionally centered around a pitch deck, but this approach has several disadvantages. This has led to the pitch deck only being a small part of a more structured data gathering process used in a digital innovation scouting process.

Pitch decks are designed to provide high level information to quickly summon interest in the reader. Most of the time they are created with investors in mind, so the financial aspects are front and center. More riskier topics (e.g. technology or market challenges) are often not highlighted or even completely missing to not impede an investment opportunity. This also makes pitch decks very hard to compare. The evaluators in later stages start long cycles of information gathering, requesting details and closing information gaps. If done at a later stage it is not as efficient than if the data is enriched at the discovery stage.

Especially with a growing number of innovation leads structured information data sets are exponentially more valuable for the evaluation phase. An innovation scout will use the pitch deck as a fast and easy tool to decide if the innovator fits the search profile, but once confirmed the lead is ushered through a process that has similarities to KYC (know your customer) used in banking.

The set of information that is collected from each lead, usually through a set of questionnaires, is refined over time but is defined by the innovation knowledge network. Because they act as evaluators in later stages, they are best suited to define what information they will need to make a decision. Basic factors such as financial KPIs will be among them, but also very domain and industry specific questions.

Obviously additional request for information during the evaluation phase cannot be fully avoided, but the dataset gathered from discovery should allow for a large part of the evaluation to be performed without further questions. Those that pass an early evaluation will then use more detailled datasets and interviews to complete the evaluation.

A modern innovation scouting solution will allow the creation and management of these questionnaires, their distribution to identified leads and manage the process all the way through to the evaluation.

Evaluation

The innovation scout acts as the facilitator in this step, but there is a heavy reliance on the innovation knowledge network used during scoping.

Although in contrast to the first phase there is an implicit order to which groups of people in the network should evaluate first. Where scoping relied on users and consumers for ideas first (to set the stage so to speak) they would be involved at a later stage. By no means should you ignore the users or consumers, but rather let more objective measures (the financials by the business experts, the feasibility checks by the domain experts and even the company strategy) decide first. An innovation that users find excellent is of no use if the financials don’t make sense or the promise cannot be fulfilled technically.

Similar to the data collection from the innovators, the evaluation data should follow a structured approach as well. In this case the expertise of the innovation team (managers and scouts) should define what evaluations should be performed and using which scales (ideally a mix of quantitative, to foster automation, but qualitative, so as to not lose the intricacies of each evaluator’s opinion).

The amount of time an innovation can be in this evaluation phase will depend on the speed of the organisation and the urgency of the innovation. But if longer cycles are necessary, it is important to maintain an active innovator relationship (especially since if you have collected all information beforehand there is less need to communicate in the early evaluation phase). The innovation scout remains the primary point of contact during this phase and should update the innovator on new proceedings and touch base regularly since innovators are prone to change and any new information should be added to the evaluation data set. Set clear expectations for the innovator about the organisation’s intentions and processes. Otherwise you may decide to proceed with an innovation after evaluation, only to find out the innovator has moved on.

This communication effort and effectively hand holding of innovators distracts the innovation scout from their core objective – finding new innovation. So although it is necessary, tooling support should be implemented to automate this as much as possible, such as informing the innovator automatically about the progress of the evaluation via email, requesting updates etc. A good innovation scouting system becomes the central hub for your innovation funnel activities.

Implementation

What comes out of the innovation scouting funnel are qualified innovations. That means they have support from domain and business experts, they fit the strategy of the organisation and have signs of early market validation. Depending on the scope they originated from and also the nature of the innovation, an appropriate implementation is then chosen.

Generally speaking, there are three typical outcomes to an innovation scouting initiative: procurement, product development, and investment/M&A. Sometimes one approach is chosen as a test and then morphs into another (e.g. close procurement partnership results in acquisition of the innovation).

During this phase a hand-off from the innovation scout, as the process lead so far, to a dedicated implementation manager occurs. This role will often still be part of the larger innovation organisation in order to bridge the different cultures that will ultimately collide, but the scouts job is done at this point.

Conclusion

Very often tools and knowledge from sales or procurement funnels are applied to the innovation scouting process without further adaptation. But innovation with it’s impact across the organisational boundary, influence from numerous stakeholders and very unique challenges simply doesn’t fit neatly into those existing templates causing the associated methods and tools to fail.

The innovation scouting process described here can be used as a blueprint to mitigate a large part of the uncertainty involved in innovation scouting. But the role of the innovation scout is central to all activities, through all phases up until innovation is implemented.

“By driving needs definition and aiming for a strong fit between need and idea, [the innovation scout] can reduce the risk of launching products that don’t sell. With organizational support and strong incentives, a formal scouting process can also effectively address internal resistance to externally-generated ideas.”

The Management Roundtable (Source)

Further reading and References

- Dahlander, L., & O’Mahony, S. (2017, July 18). A Study Shows How to Find New Ideas Inside and Outside the Company. Harvard Business Review. A Study Shows How to Find New Ideas Inside and Outside the Company